Poker & Pop Culture: David Mamet's Card-Playing Con Artists

The American playwright, screenwriter, and director David Mamet has a long, four decade-plus list of artistic achievements marked by numerous highly-regarded plays and films. He's earned numerous Tony nominations as well as a Pulitzer Prize for his 1983 play Glengarry Glen Ross (successfully adapted into film in 1992).

Mamet is thought by many to be one of the most important dramatists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries with his plays considered alongside those of Arthur Miller, Edward Albee, Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Tom Stoppard and the like. Mamet's plays and films are often populated by a variety of con artists and hustlers �� and, of course, those on the losing side of such schemes �� through whom he cynically explores the so-called "American dream."

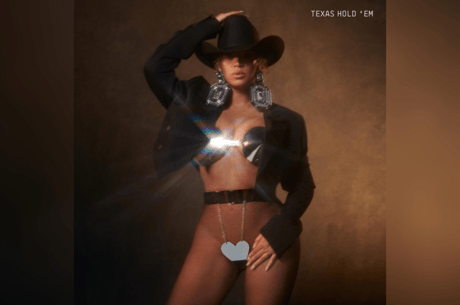

Mamet is also a dedicated poker player, having written directly about the game while memorably incorporating poker into some of his plots. It's only fitting, really, that a writer whose characters so often can be found employing deceit and trickery in order to gain from others would be attracted to the bluffing game.

Mamet's most direct discussion about poker appeared in a New York Times Magazine column in 1986. Poker games also prove central to a couple of his most accomplished and well regarded works �� his early play American Buffalo and his directorial debut House of Games.

Indeed, both stories in different ways support Mamet's more direct statement of what makes a winning poker player.

"The Things Poker Teaches"

The title of Mamet's short NYT Magazine essay characterizes poker as a game that provides learning opportunities to those who play it. Poker, he maintains, teaches us "things" about ourselves and about human nature, generally speaking. It's a game that can also make us better at what we do away from the tables, too.

If we're paying attention, that is.

Mamet starts out distinguishing between winners and losers, then focuses on how "poor winners" are those who mistakenly "attribute their success to divine intervention and celebrate either God's good sense in sending them lucky cards or God's wisdom in making them technically superior to the others at the table."

Good winners don't crow about it when they win. Nor do they walk away satisfied with having won and think the positive result means further self-analysis is no longer needed.

"The poker players I admire most are like that wise old owl who sat on the oak and kept his mouth shut and his eye on the action," Mamet writes.

Good winners play a detached game, able to "look forward to the results... with some degree of impassivity." They make consistently good decisions, and as we've heard the most successful pros say time and again, don't worry about what happens thereafter when the cards may or may not reward such good decisions with positive results.

"When you are so resolved, you become less fearful and more calm. You are less interested in yourself and more naturally interested in the other players: now they begin to reveal themselves," he explains.

"Poker reveals to the frank observer something else of import �� it will teach him about his own nature."

Good players have no problem with this truth, but "bad players do not improve because they cannot bear such self-knowledge." They get distracted by the pain of losing, and fail to be rational enough to recognize the reasons why they are losing.

Good players are able to take in stride the fact that poker teaches us things about ourselves, including our limitations or other things we might not be so comfortable knowing about ourselves. Meanwhile, bad players prefer not to know �� as though they prefer looking away from the mirror the game provides to us.

Mamet concludes by referring to the fact that over many years of playing poker he's gotten better, and "that improvement can be due to only one thing: to character, which, as I finally begin to improve a bit myself, I see that the game of poker is all about."

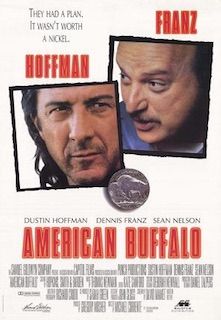

American Buffalo

During the early 1970s when Mamet was a budding playwright teaching drama, he spent eight hours a day playing in a poker game in a junk shop in Chicago. It was that experience that helped inspire his early play American Buffalo that premiered in 1975, made it to Broadway a couple of years later, and was among a trio of early works by Mamet that helped to establish him as a formidable talent. It was later adapted for film in 1996, with Mamet writing the screenplay.

The two-act play entirely takes place in a junk shop and features only three characters, giving it an intimate feel that isn't too different from looking in on a three-handed game of poker. And in fact, a poker game from the previous night serves as an important context for the story, as does the earlier sale of a Buffalo nickel by the shop's owner to a customer a few days before.

We learn early on how Donny, the owner, sold the nickel for $90, though now suspects it might have been worth much more �� "five times as much," he thinks.

Those misgivings inspire a plot that initially involves young Bobby, employed by Donny to spy on the comings and goings of the customer who lives just around the corner. The original plan is to try and steal the coin back, but when Donny's poker buddy, Walter �� a.k.a. "Teach" �� gets involved, the idea broadens to a larger scheme to steal even more. (Mamet also earned the nickname "Teach" in the junk shop poker game he played.)

There is a regular poker game at Donny's junk shop, and talk about last night's game reveals another character named Fletch had been the big winner, taking away $400 from the game. Reflecting Mamet's idea that being good at cards is directly related to strength of character, Donny and Bobby speak admiringly of Fletch.

"Fletcher is a standup guy... he is a fellow who stands for something," insists Donny. "He's a real good card player," says Bobby. "This is what I'm getting at," Donny continues. "Skill. Skill and talent and the balls to arrive at your own conclusions."

Donny's admiration of Fletch (who never actually appears in the play) alters his plans as he attempts to involve him in the robbery scheme. But that idea gets muddled when Teach alleges Fletch is a cheater, supporting his accusation with a story of his having witnessed Fletch cheat the night before in a hand in which Donny lost $200.

In the five-card draw hand, Teach had folded predraw while Donny stood pat on a straight and Fletch drew two cards. Fletch ended up winning the big pot with a heart flush, king-high.

"I swear to God as I am standing here that when I threw my hand in when you raised me out, that I folded the king of hearts," Teach maintains.

The revelation changes everything, and also inspires suspicion that young Bobby might be keeping an alliance with Fletch hidden from Donny and Teach.

Bobby denies any such alliance, but is he bluffing? Is Teach bluffing about Fletch having cheated? Donny simply doesn't know �� he isn't a good enough poker player to figure it all out.

Donny's confusion about the Buffalo nickel and what it might really be worth is similarly clouded by his own inability to recognize his own limitations. He knows the prices listed in a coin book are only a starting point for negotiations. "The book gives you a general idea," he says. And he readily agrees when Teach points out "you got to have a feeling for your subject" when it comes to applying that general idea to specific situations.

But Donny doesn't realize he doesn't have that "general idea" or "feeling" that someone with more experience and knowledge �� like a winning poker player �� would have. Not with the coins, not with the people with whom he's dealing.

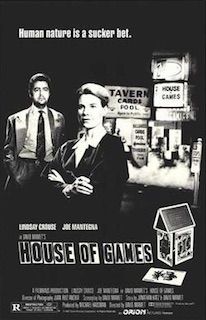

House of Games

Mamet's directorial debut, House of Games (1987), is also about bluffing and how people deceive one another, as well as why people fall for such deception time and time again. It likewise uses poker as a way of introducing themes elaborated upon more thoroughly by the film's larger plot �� in this case a more ambitious, complicated "confidence game" in which a group of con men target a female psychiatrist named Margaret Ford (played by Lindsay Crouse).

One of Margaret's patients, a gambling addict named Billy, criticizes her profession �� calling it a "con game" �� then informs her he owes a man named Mike $25,000 and will be killed if he cannot pay the debt in one day. Margaret decides to try to help her client, perhaps urged to do so by his insistence that she can't help him in their session.

She visits a pool hall called the "House of Games" where she confronts Mike (Joe Montagna) who tells her Billy actually only owes him $800. He then invites her to observe him playing a poker game in a back room, getting her to agree to help him beat another player in the game, George (played by the magician and famous card-trickster Ricky Jay), in exchange for forgiving Billy's debt.

There ensues a lengthy poker scene revolving around a single hand. (As explained on the DVD commentary by Mamet, the actors come from a high-stakes game in which he himself participated for many decades.) George has a tell, Mike informs Margaret �� he plays with his ring when he's bluffing. But George knows Mike has discovered the tell and so now avoids doing it. Mike contrives to make a restroom visit during a big hand, asking Margaret to watch for the tell in his absence.

The game is five-card draw, and a hand arises in which Mike ends up with three aces while George has drawn one card. After George only calls a third player's pot-sized postdraw bet, Mike raises, the original bettor folds, and George reraises an additional $6,000 �� money Mike doesn't have. That's when Mike visits the restroom, and while he's gone Margaret spots George fiddling with his ring �� the tell.

Mike returns, Margaret lets him know of the tell, and since she's so confident George is bluffing she offers to cover the additional $6,000 if needed. Mike calls, George shows a flush, and Margaret is out $6,000.

As it turns out, the entire poker game is one big setup �� a con in which Mike, George, and everyone else is involved and Margaret is the "mark." It nearly works, too, until George draws a gun pretending to be angry at Mike's slowness in settling, and water drips from it to reveal it is a water pistol.

Rather than be upset at having been nearly tricked, Margaret's fascination at the entire scheme overwhelms her. (The fact that Mike agrees anyway to forgive Billy's debt also helps assuage her.) She's inspired to write a book about the con men, and soon gets romantically involved with the dangerous and debonair Mike.

As you might guess, from there the "games" continue, and the plot becomes ever more complicated as Margaret naively finds herself under Mike's spell. She's not unlike Donny in American Buffalo �� caught in a game she doesn't completely understand, with her own reluctance to realize her limitations as a "player" further impeding her ability to compete.

Mike might be a "bad guy," but he's an unequivocally good player. At one point he tells Margaret why he thinks she's attracted to him, his words echoing Mamet's description of a winning poker player.

"I think what draws you to me is this �� I'm not afraid to examine the rules, and to assert myself," he says. It's an expression of confidence befitting the "confidence man" that he is. He's saying he knows what the correct decisions are and is more than willing to act upon them.

"I think you aren't, either," he adds, telling Margaret that she, too, isn't afraid to question and probe and to assert herself where needed.

But is he bluffing?

Conclusion

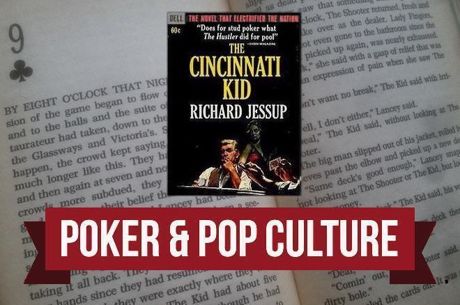

Even where poker isn't being played on the stage or on screen, Mamet's stories often present situations in which characters are playing partial information games with one another, constantly seeking "tells" and trying to suss out "bluffs" with some being more successful than others.

Those who are more successful typically exhibit the same qualities as those who win consistently at poker. They've been able to pay attention and acquire knowledge. They are like Fletch as Donny describes him early in American Buffalo, the line humorously hinting at the intrigue involving a coin that follows: "You take him and you put him down in some strange town with just a nickel in his pocket, and by nightfall he'll have that town by the balls."

Rather than overlook their own deficiencies, good players �� winning players �� address them squarely and work to improve where needed. In other words, they learn to stop tricking themselves, which helps them become better at tricking others.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America's Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.